|

Chapter 1. Basic Principles

of Political Phenomena

A. General Principles of Political

Phenomena

(3) Basic Theory of Mathematical

Politics

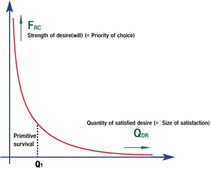

c. Desire Quantity and Will to Struggle

Generally,

people's desires are short-term stable. In this case,

what is stable is the total quantity of desire. People

want a certain amount of food and drink, a certain

level of safety, and a certain level of entertainment.

They want a certain level of freedom and comfort. Generally,

people's desires are short-term stable. In this case,

what is stable is the total quantity of desire. People

want a certain amount of food and drink, a certain

level of safety, and a certain level of entertainment.

They want a certain level of freedom and comfort.

The desire for fulfillment decreases if the desire

has already been fulfilled in large quantities, due

to the consistency of desire quantity. On the other

hand, if the desire has only been fulfilled a little,

the desire to fulfill it further remains very strong.

Therefore, it can be concluded as follows:

| |

[Ch.1.7] (Consistency

of Desire Quantity) People's desire becomes stronger

when it is less fulfilled; and weaker when it

is more fulfilled. |

Most people have a certain level of

desire, and when food is scarce they strongly desire

food, but once they have eaten enough, they desire

it less. So when their stomach is full, food is no

longer used to satisfy hunger but for other purposes,

such as a tool for sensory stimulation. Similarly,

most people desire freedom, but once they have obtained

a certain level of freedom, they tend to just follow

the choices of others and desire to be restrained

enough.

The consistency of the desire amount

refers to the same thing as the law of diminishing

marginal utility that is mentioned in economics. This

is because the will to satisfy a certain amount of

desire weakens as the desire weakens, meaning that

the utility decreases. However, the fundamental assumption

is somewhat different and the mathematical models

that follow it are also different.

If the amount of desire satisfaction

( )

and the intensity of desire ( )

and the intensity of desire ( )

can be properly quantified, the relationship between

the two can be expressed in the following equation.

(In the context, they will be represented as 'Qdr'

and 'Frc', respectively). )

can be properly quantified, the relationship between

the two can be expressed in the following equation.

(In the context, they will be represented as 'Qdr'

and 'Frc', respectively).

| |

[Fmla.1.8] |

|

( is a constant) |

This equation expresses the consistency

of desire quantity[Ch.1.7]. It means that humans do

not want something A infinitely, but that when they

do want A, despite their strong desire, they are not

able to act as strongly. For example, many people

always want more money, so they earn money and still

have an insatiable desire for money, but they do not

work as desperately as they did when they were poor.

This equation can be simply transformed

into an inverse proportion equation.

| |

[Fmla.1.9] |

or  |

Its representation by graph is as

follows [Diag.1.A].

[Diag.1.A]

Strength change of desire (will to struggle) according

to the quantity of satisfaction (survival condition)

On the other hand, the unsatisfaction

of desire, i.e. the less quantity of desire satisfaction,

implies that the survival condition is bad, and the

high degree of desire strength implies that the person

has a strong will to struggle. Therefore, the consistency

of desire quantity generates the following phenomena:

| |

[Ch.1.8] The worse

the survival condition becomes, the stronger the

will to struggle becomes. Conversely, the better

the survival condition becomes, the weaker the

will to struggle becomes. |

An example from early 19th century

Russia in the reign of Alexander I, when the construction

of military settlements (voennye poseleniia) was attempted

but abandoned due to harsh survival conditions, demonstrates

that harsh survival conditions lead to strong survival

instincts. The military settlements were unbearable

due to oppressive policies, even down to the most

detailed aspects of the regulation, including the

most brutal repression. The harsh living conditions

ultimately led to a strong backlash, which was a survival

struggle. The Consistency of Desire Quantity played

a role in the causal relationship between World War

I and World War II. After World War I, the harsh,

retaliatory nature of the war reparations imposed

on defeated Germany at the Paris Peace Conference

severely damaged the German economy and made living

conditions extremely harsh, leading economists like

Keynes to predict another war. Ultimately, this led

to the outbreak of World War II.

<Every footnote was

deleted from the book>

|